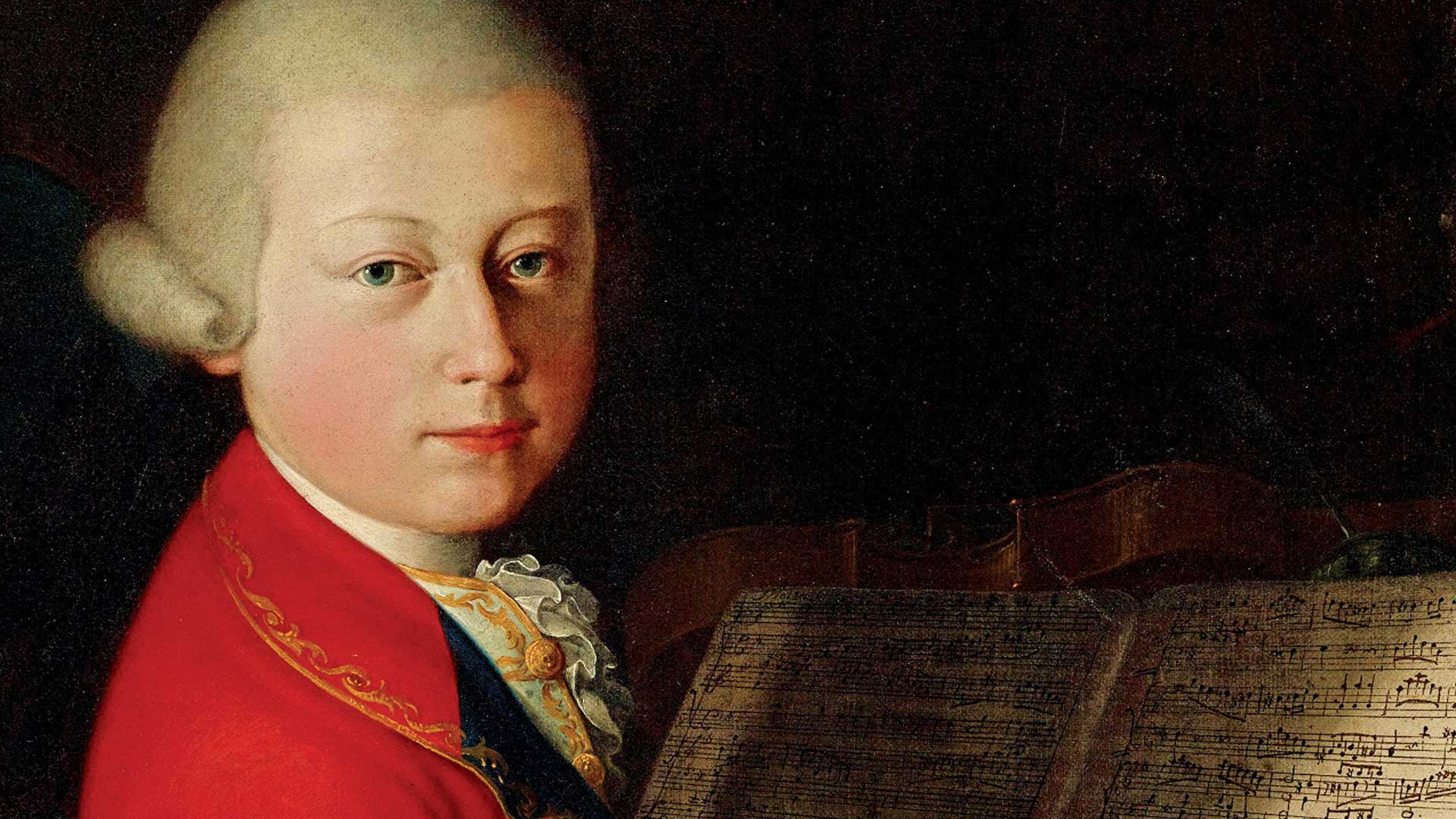

Picture this: Vienna, late autumn, 1791. Mozart has just finished The Magic Flute, he’s working on the Requiem (which he will never complete), and amid this storm of genius and urgency, he writes —in just ten days— one of the most modern pieces ever conceived: the Clarinet Concerto in A major, K. 622.

Two months later, Mozart will be gone. But before that, he gifts the world a masterpiece that still resonates today like a film score from the future.

It’s his last composition for a solo instrument, written for his friend, clarinetist Anton Stadler —a brilliant, slightly reckless innovator who loved experimenting with new sounds. He would go on to develop the basset clarinet, an extended version of the traditional instrument capable of reaching deep, velvety tones that seem to hover somewhere between melancholy and dream.